‘The swan flies alone

The swan is its own song.’

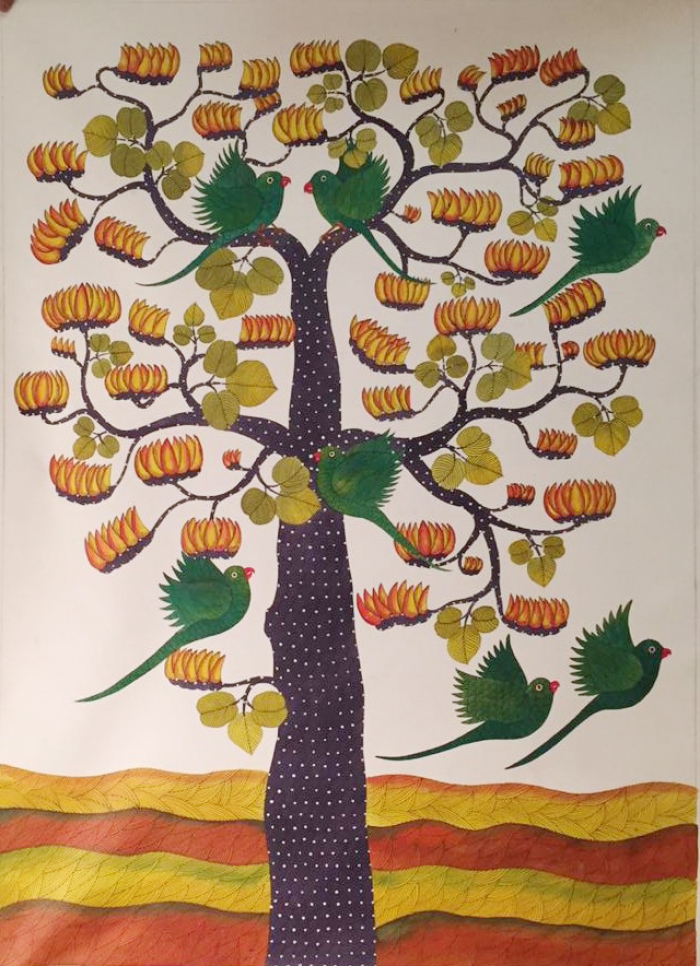

The winding roads past the shimmering lake are dotted with Tesu trees bright with rust and orange blossoms. The roads are strewn with flowers that have fallen off the trees, their petals turning shades of brown. In Bhopal, the remains of Holi celebrations are visible everywhere, on walls, faces, and buildings, smears of colour remain like a lasting memory of the festival. Venkat grins broadly when he talks about the festivities in his village; he made it back home in the late hours because of pending deadlines, otherwise, there was no way of knowing how long the celebrations would continue. As we make our way to his studio, he tells me how the Tesu flowers are an intricate part of ‘Phaag’ or Phagun/Spring and how the songs celebrate this beautiful flower, which is also given in offering to the god, Hola. Venkat has a vast repertoire of stories and songs, this time because Holi is just over, and the subject is the Festival of Spring.

In his village, as a boy, learning about colours and lines made more sense than learning the alphabet and numbers. Sijhora had a school but he often played truant, preferring to play in the woods, instead, or paint. When he had chanced upon his maternal uncle, Jawahar’s paintings in an old trunk at home had opened up a new, enchanted world. Unbeknownst to the elders, he pored over the sheaf of sketches, determined to try his hand at it. The lack of materials did not deter him, he filled the walls, floors and discarded newspapers with his scribbles in charcoal only to get a severe beating for his artistic endeavors! Not perturbed in the least, he continued to pursue his passion till, his drawings caught the attention of his uncle, the well-known Pradhan Gond artist Jangadh Shyam. Jangadh was a celebrated artist, not just in Sijhora or Patangadh, but also throughout the State having recently been honoured by the prestigious Madhya Pradesh Shikhar Samman (1986). Impressed by the young boy’s skill and much to Venkat’s delight -- Jangadh invited him to Bhopal.

For the fledgling artist who had grown-up amongst the woods and streams of his village, Bhopal was the Rajdhani. Not having stepped out of Sijhora, he was extremely excited and remembers having conjured visions of magnificent palaces and courts ruled by a powerful Raja; because surely that was how all Rajdhanis were meant to be? To his astonishment, the Railway Station bustling with throngs of people, though not at all what he had expected had a certain excitement and energy that thrilled his senses. He felt he belonged. With a great sense of purpose, Venkat prepared himself to work under Jangadh till he met other artists at Bharat Bhavan, notably J Swaminathan who encouraged him to build his artistic career. While he worked tirelessly, learning new techniques and exploring new forms, getting used to the city life, his village remained in his heart. The dense forests of Kanha, the deer, and birds he had seen, now became a part of his pictorial narrative. And in the midst of his compositions, a boy appeared, chopping wood, grazing cattle and tending to the fields. Venkat’s visual memoir was already drawing from his childhood years, his own life and that of his close friends, Pusaam and Dhurve, Bana players who sang melodiously of love and loss. Yet, life in Bhopal, exhilarating with the promise of romance and success, was exciting too. The boy who had never seen an auto-rickshaw now wanted to travel by aircraft (in those years Bhopal had one flight a week!). Through the struggle to learn and earn a little money, there were also happy times, too, when his companions and he cooked together and sang Dadariya folk songs. The fragrance of the earth, the song of the Tiltila birds and legacy of the land is what makes Venkat’s work so richly layered and fascinating. When the artist narrates the story of Eklavya or Shiv Parvati, the dramatis personae appear distinctly human with flaws and eccentricities that one can relate to.

In his late 40s now, Venkat Raman Singh Shyam has been showing in India and abroad, participating in significant exhibitions. Despite his success, deep inside, the artist is restless and concerned about the immense environmental crisis we are heading towards.

‘Earlier there was green everywhere you looked but now, no more. There is rapid deforestation that is devastating our land, riverbeds are turning dry and animals and birds are starving. Unless we address this crisis immediately, it will be too late. Prakriti is our teacher, we need to respect and protect our environment’, he says.

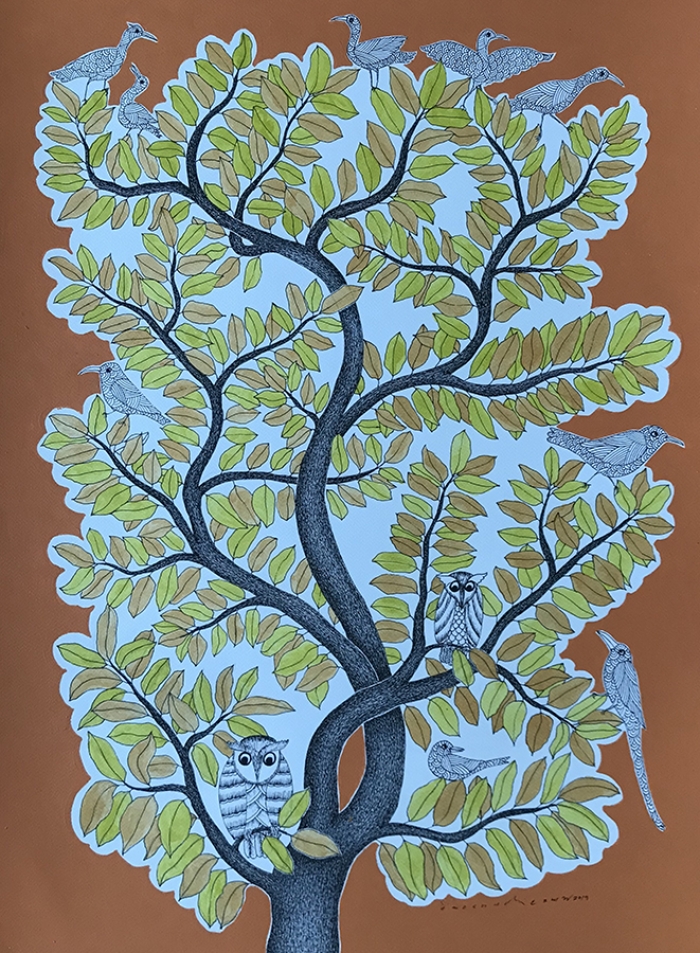

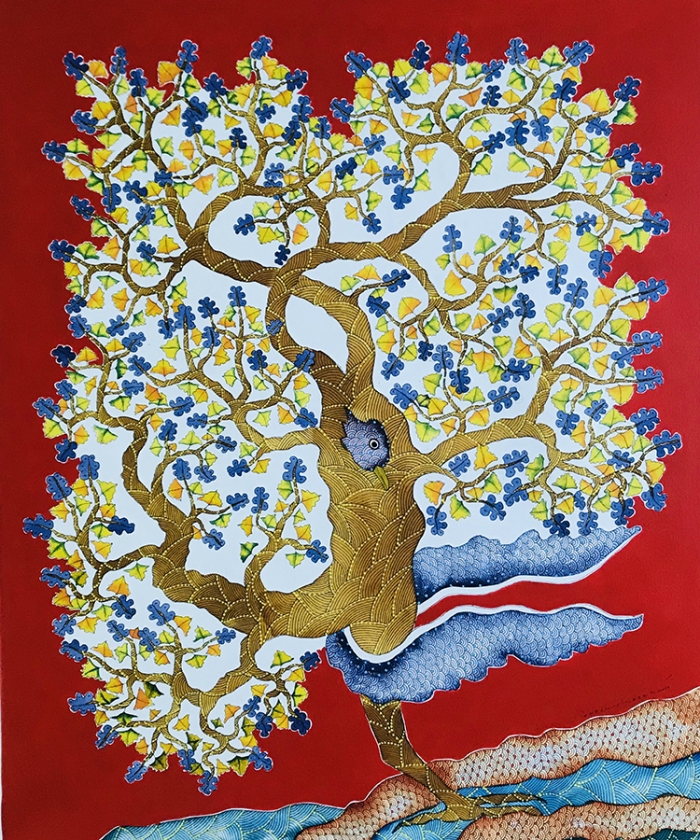

In his imagination, the legends and fables associated with the gods and demons, trees and rivers, birds, beasts and reptiles have always played a vital part in his art, the songs he had heard, a distant memory of boyhood remained in his heart. Yet, their visual form transformed time and again, reinventing themselves in different avatars. In image after image, Venkat’s deep involvement with the natural environment expressed itself. As an artist he never strayed far away from his roots; despite his relocation to the city, he is proud to say that he belongs to his tribal community. In the imaginary world of his enchanted forests, myths and nature coalesce and create an atmosphere that is evocative and sensuous.

The ornate patterning and decorative motifs we see in his present work show his evolvement as an artist who has chosen to consciously align himself with the contemporary. The primeval elements are now subsumed under modern sensibilities, the motifs and textures now appear more stylized in the way he visualizes the forms. In the paintings, the trees are a part of a larger forest, familiar from his memories. They had wandered around the forests once, grazing their cattle and collecting firewood and wild berries, mindful not to upset the many gods and demons that were known to roam there. On festive occasions, the communities used to gather, to venerate and worship the divine spirits with ritual and song. The present pictorial space evokes those faraway times and conveys the cultural beliefs and faith that were such an intimate part of his life. Yet the trees are being felled, the birds have flown off to other places and sing no more. Venkat transforms the real and the memory world into the core of his work; it is against this personal history that we must view the works, layered with the nostalgic reflections on what was once the migrant’s beloved homeland.

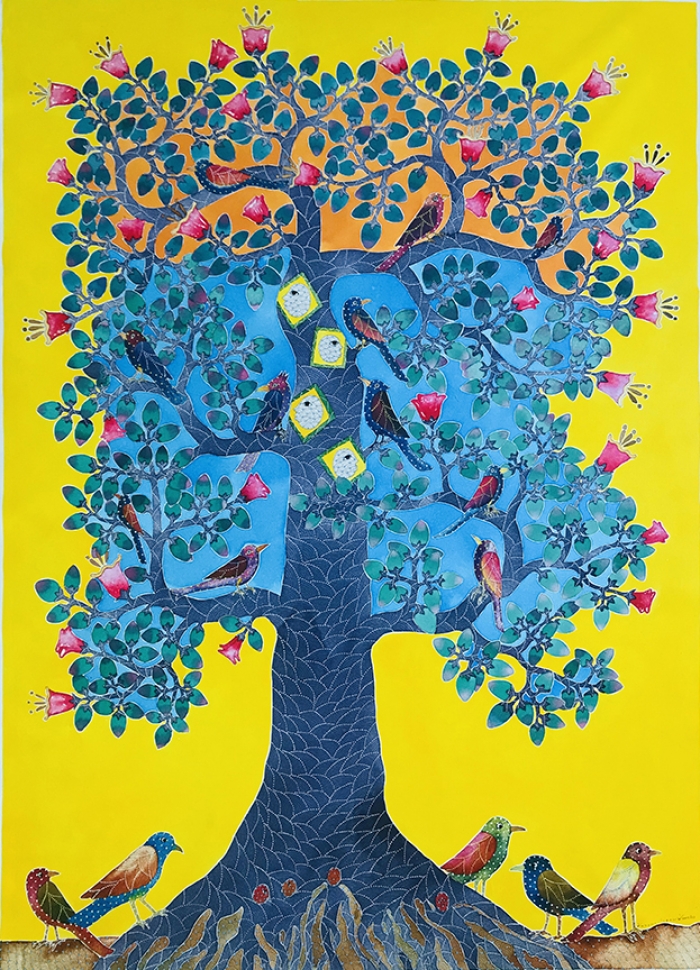

Tree of LifeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Tree of LifeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Tree and BirdVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Tree and BirdVenkat Raman Singh Shyam TesuVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

TesuVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Silk Cotton Tree and WoodpeckerVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Silk Cotton Tree and WoodpeckerVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Shelter 1Venkat Raman Singh Shyam

Shelter 1Venkat Raman Singh Shyam Semal TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

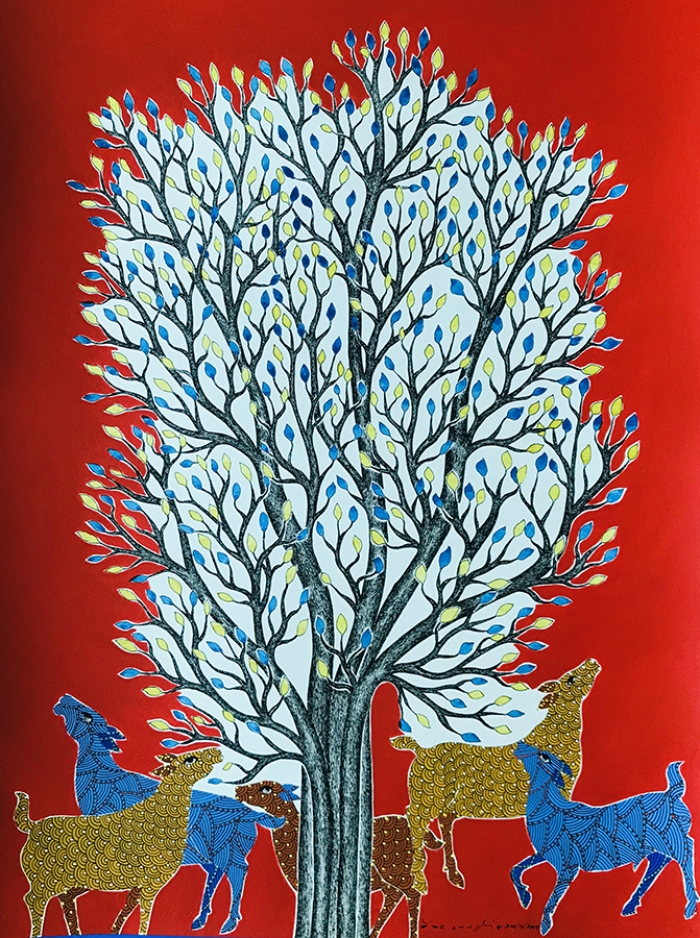

Semal TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Peepal TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Peepal TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Pakari TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Pakari TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam OwlVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

OwlVenkat Raman Singh Shyam NandiVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

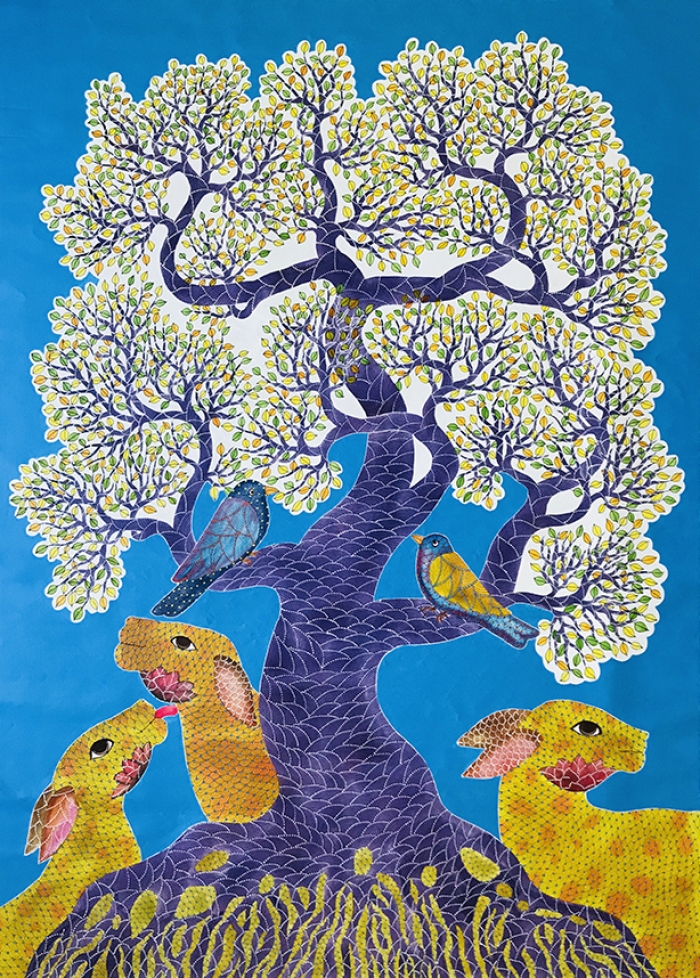

NandiVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Knowledge TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Knowledge TreeVenkat Raman Singh Shyam GaurdaVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

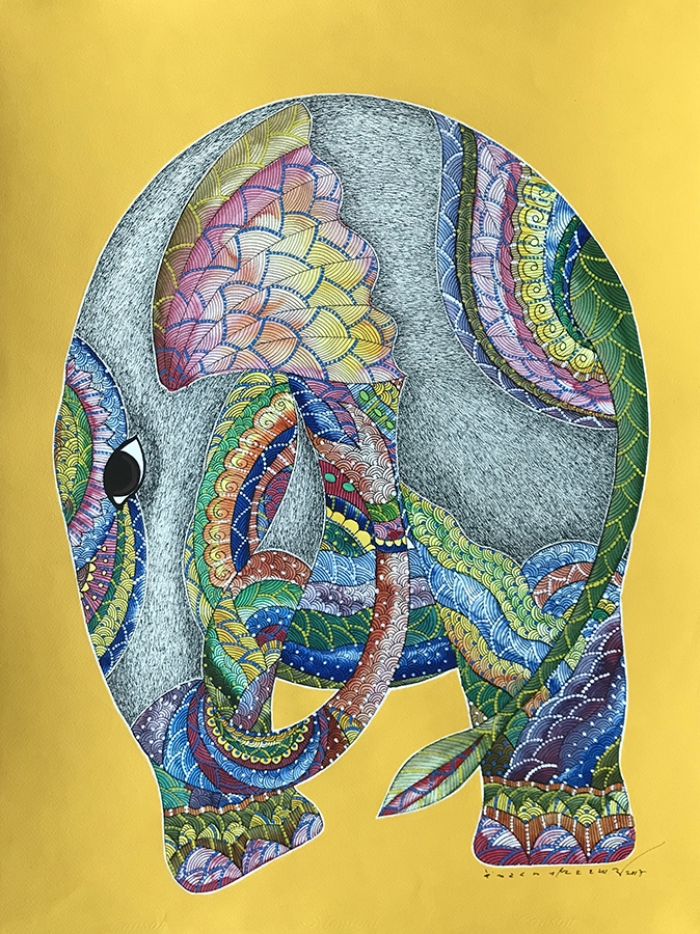

GaurdaVenkat Raman Singh Shyam ElephantVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

ElephantVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Dancing PeacockVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Dancing PeacockVenkat Raman Singh Shyam Bagh DevVenkat Raman Singh Shyam

Bagh DevVenkat Raman Singh Shyam