As social and political battles rage over the creation of a separate state for Telengana, till now a part of Andhra Pradesh but with its own cultural intonations, one person at least has already created his own Telengana universe. It is idyllic, true, perhaps even mythical and, given that it is slipping away fast, almost certainly nostalgic. Like the people of Telengana, he is contented, happy to let life pass him by, ensuring the sanctity of his siesta, reluctant to move out of the comfort zone of friends and habits earned over a lifetime, preferring the company of people he has ‘created’ over five decades – loyal companions who have never deserted him, and whom art-lovers know as artist Thota Vaikuntam’s emblematic Telengana men and women.

And yet, Vaikuntam is changing. But to understand how, you have to understand, first, who Vaikuntam is and what keeps him ticking?

Ask him and the artist whose works are part of collections worldwide will humbly say, “I am a farmer.” It is true that till recently he tilled the land on his farms, but growing up as a child in a Telengana village, he was desperately poor, his family ran a small village shop, he would paint and draw the male impersonators in local theatre groups, and probably spent his free time teasing village girls, as groups of village boys are probably still wont to do. He may yet consider himself a farmer, somewhat bemused by his own fame as an artist, but there’s no escaping the pressure on him to produce more work as collectors demand his paintings, making it almost impossible for him to bring about a change in his practice.

And yet, in this, his recent body of works, he has managed to do just that.

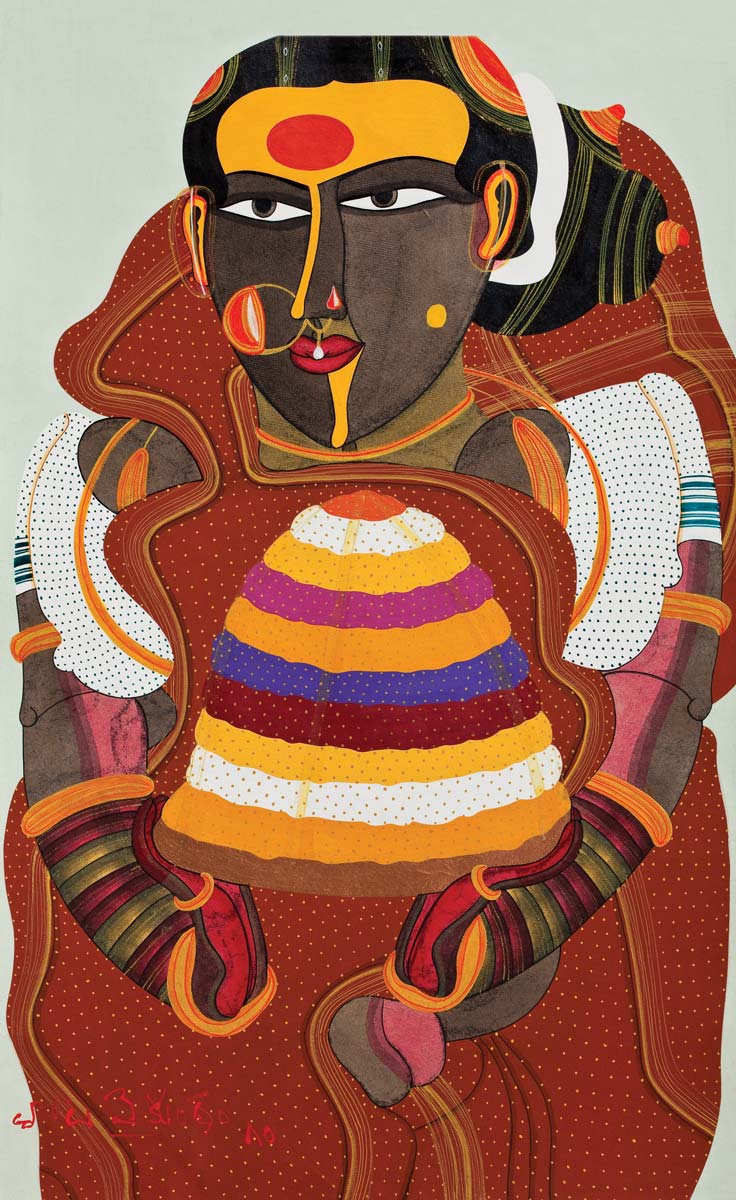

But to understand the transmutation, you have to understand the environment and the style that he created for himself as his signature, and which became an iconic leitmotif. His inspiration and model, he will readily admit, was as much his mother as it was the women he saw all around him in his native village – sturdy, hard-working women with glistening, dark skins and supple bodies, not so much willowy as corpulent, but with an inherent, almost indolent sexuality that was part of their brightly-coloured bodies and bindi-painted foreheads. They wrapped themselves in sarees in a manner that was stimulating, flashed a wicked navel, used their bangles and nose-pins like weapons of seduction, but it was a part of their everyday armature and not something that was selectively inviting. But in accessorising themselves, they established a physical presence that resulted in a frisson of sexual tension just by their being.

Vaikuntam’s men suffered by comparison, often just lending support to a composition, the weaker of the two in the relationship for they did not appear in command in the same manner as the women did. Even though the women were companions and care-givers, housewives and tillers, they seemed imbued with a sense of majesty, allowing them to be drawn to but detached from their male counterparts. But if there was a suggestion of conflict between the two – as there is in most relationships, and which artists are quick to latch on to – then in his new manifestation, Vaikuntam has obliterated it to cast his protagonists in a new mould. No longer is there a sense of disharmony in their liasion, no more are they competitors but, instead, are co-conspirators, in perfect affiliation, in a state of sublime harmony.

But, again, we are getting ahead of ourselves.

It has been some time since Vaikuntam has felt the need to document the vanishing universe of his native Telengana. In many ways, he has already achieved that. The unique manner in which the women drape their sarees – drawing its length between their legs so that their hips are made prominent, a devise Vaikuntam has used provocatively – the markings of turmeric most notably on their forehead, nose and chin, the body postures as they stand around gossiping, or when going about their chores, the suggestion of the task at hand through the use of a symbol – a kamandal, or manuscript, for a priest, a trumpet for a musician, a turban for a farmer – are all things Vaikuntam has cast in his canvases: repeatedly, according to some, though the experience of each portrait, each subject, is visually, and viscerally, different.

Hints that he would like to develop beyond his established boundaries have appeared frequently, and most exceptionally in his ability to capture a strand of music in some of his canvases, the suggestion of some festivity in others. But both these worlds remained elusive as patrons kept pushing him for more works of a nature that already existed, and which they coveted, leaving the artist with very little time in which to develop a new identity.

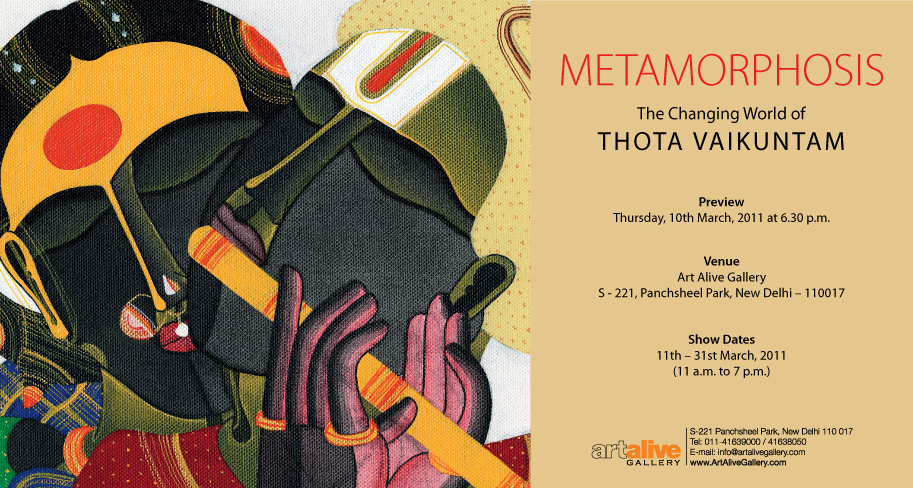

With Metamorphosis, ThotaVaikuntam can claim to have traversed that distance too. Metamorphosis marks several changes in the artist’s career. There is the change in him and his work, and there is the transition in his characters. It is time, now, to tell that story.

It all begins with music in his village, as indeed in all the villages of Telengana, he says; music that is not of the high, classical breadth of, say, flautist HariprasadChaurasia, but music that plays in the hills and forests and fields of this ancient land, as natural as the trees and the women in their resplendent sarees. “It is the sort of music that pleases us villagers,” he says modestly.

Many, if not most, villagers respond naturally to the sound of the flute, and several can claim to play at least a few simple notes. “Every child in the village plays some instrument,” he tells you. And Vaikuntam’s muse here is a village lad called Vijay, “a pure villager, a character from my village” who, improbable though it might sound, Vaikuntam has cast in the character of Krishna. The divine cowherd was never far from his flute, and in Vijay, Vaikuntam sees the same quality. “He is my Krishna,” he says – no, not Vijay, in whom he simply sees a model for his rendition – but his painted character that represents the cowherd lord. There is still the pictorial vocabulary of the familiar Telengana man about his Krishna, in the pleats of his dhoti and the markings on his forehead, but this is a more refined version, almost as though Vaikuntam has risen to a more spiritual plane as an artist.

“The concept was a series on music,” he explains, but it morphed, somewhat unexpectedly and beyond his control to an expression of Radha and Krishna. If the subject chose itself, Vaikuntam is amazed at how the works compelled him to work harder, more diligently, on his nuances. “The compositions are more delicate,” he critiques his own work, “the lines are more robust, the quality of finishing has improved.”

Indeed, as you look at the new body of paintings, you cannot help but be moved by the melding of the male and the female into a single entity, of their apparent juxtaposition and merging, almost as if in so rendering them, he was casting them as Ardhanarishwar, the male:female protagonists, whole by themselves but strangely incomplete without their masculine:feminine counterparts, which, the scriptures tell us, are as much a part of all our beings as it is of yin:yang the universe, but which we, in our individuality and in searching to establish differences, have found difficult to reconcile. The portraits might be individually independent, yet they are composed in such a way that it is difficult to view the man as separate from the woman, and vice-versa – for each completes the other.

There is the suggestion of bhakti-ras in these works, you tell him, the notes of spirituality in which one can submerse oneself. “Achieving that was the main thing,” he acknowledges somewhat ruefully. In many paintings, the men and the women – those playing the flute or listening to it – have their eyes shut, you point out to him, an aberration from his earlier works. “When you play, or listen, you close your eyes in concentration,” he tells you, though the sense you have as a viewer is of a complete merging that requires the total annihilation of the self, of submission and sublimation. “There is,” he agrees, “a sense of the feeling of ecstasy.”

Ecstasy. That, you agree, is the elusive word that defines his current mood.

If the music player is his Krishna – the lover, you suspect, that exists in all men – then “Radha is every woman who is in love with him because he is charming, but also because he is such a great musician”. But his ode to music is not merely to show Krishna as a performer, but Radha as someone who can take the flute to her lips just as easily, and be her own beloved, making it a challenge for Krishna to woo her. In mischievously passing the flute like a baton between the two, he has managed to insert a playfulness into their role-playing.

Also noticeable in several images is the parrot – Kama’s messenger. Is it a devise to deliberately bring cupidity and romance into the composition? Vaikuntam muses a little, thoughtfully shakes his head. “Yes, the parrot is associated with the god of love,” he says, but that is not the reason it appears in his paintings. “I think the parrot can express feelings of love through its very presence,” he explains – perhaps by standing in for Radha in her absence, or to act as a device that allows the painter to communicate the emotions of the two lovers. “It is representative of their love, yes,” he agrees, but the reason for the bird’s presence is also somewhat more ordinary and prosaic. “Most village women have symbols – weaves, embroideries, jewellery – of the parrot in their apparel, which depicts their affection for it.” Vaikuntam has merely used the form of the bird as an expression of those emotions in this series.

With the compositions having grown more delicate, even perhaps piquant, Vaikuntam has intentionally lightened his palette too. The colours are still bright and contrasting, but there now appears to be a greater sophistication in their application – almost as if Vaikuntam is renouncing the temporal for the spiritual.

But this is unlikely to traverse as part of his ongoing body of work, especially if the seed for the genesis of his next body of work lies in this one. Part of this series, but already unfolding along a new path, is another documentative study where the robust line is back, and the colours are brighter, the corpulence once more in evidence. Eyes kohled, their lips prominent, their massive hands holding up cones of flowers, these are women out to pay homage to Bhatkamma, the festival of flowers that occurs just before Dussehra. “I want to record the uniqueness of the festivals of Telengana,” says Vaikuntam, “before they are lost forever” – for the artist’s idyllic world is already collapsing around him, a victim as much to creeping urbanisation as it is to modernisation. “Already,” he laments, “they are changing, getting lost – no one remembers these things any more.”

No one but those few who moan its passing and recreate it as a slice of life and so bring joy to the lives of millions as renditions on paper and canvas, somewhat caricatured, but true in intent. It is a world of rustic simplicity, not entirely bereft of its rituals – but in the musical cadences that Vaikuntam captures to convert into his enchanted telling of Radha and Krishna, he is paying ode not just to a time-tested story but to the regional lores of his beloved Telengana.

The muse has morphed slightly and the artist’s brush has recorded the change with a subtle shift in its rendition, but the portraits remain unchanged in their iconic stature. In that invincibility eventually liesVaikuntam’s strength as an artist.

– Kishore Singh

Delhi, 2011

UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam UntitledThota Vaikuntam

UntitledThota Vaikuntam